Source: firstpost.com

Earlier this year, as the glitzy Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) came to a close, preparations were in full swing for another such event titled Gateway Literature Festival (GLF), which held its fourth edition a few days later in Mumbai. Still young and with an acronym that is perhaps unintentionally similar, GLF is beginning to get its share of attention. The buzz around the festival is, of course, well deserved, for GLF is doing great service to the Indian literary scene by shining the spotlight on writers of regional literature.

While the JLF has grown to become the New York Fashion Week of literature festivals with celebrity writers (sometimes, more celebrities than writers), the GLF is turning its gaze towards earnest practitioners and their mother tongues. The 2018 edition featured over 50 writers in languages such as Assamese, Ahirani, Bengali, Bhojpuri, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Khasi, Kashmiri, Konkani, Kosali, Malayalam, Marathi, Manipuri, Maithili, Odiya, Punjabi, Sindhi, Telugu, Kannada and Tamil. By packaging the mission of older, more revered institutions such as the Bharatiya Jnanpith and the Sahitya Akademi, in a contemporary format, the GLF hopes to draw the attention of readers once again, towards stories of the soil.

Their time in the sun

While GLF works towards recognition, publishers and translators are working fervently towards access. Big publishing houses such as Penguin, HarperCollins, Random House, Hachette, Oxford University Press, and Rupa have joined forces to serve Indian English readers the many flavours of regional literature. Other smaller publishers such as the Seagull and Aleph are fondly partial to translations. Though pegged at just 3-4 percent of the output of the Indian publishing industry, translated works are slowly beginning to capture the imagination of readers.

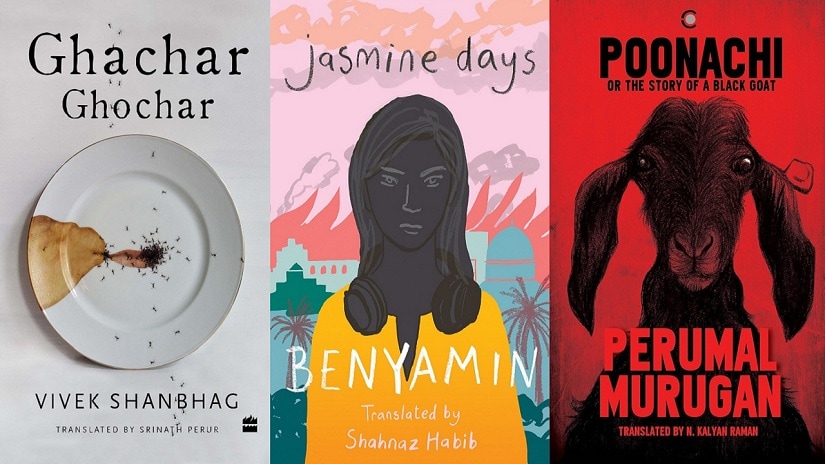

Recognition from other platforms such as the JCB Literature Foundation helps the cause some more. It is heartening to see that the recently released shortlist for the prestigious JCB Literary Prize for Literature features two works of translation. As Perumal Murugan’s Tamil novel, Poonachi, translated by N Kalyan Raman, and Benyamin’s Malayalam Jasmine Days, translated by Shahnaz Habib, vie for top honours, readers are already propelling these books to the top of bestselling lists.

Last year, when Vivek Shanbag’s Kannada novella, Ghachar Ghochar, translated by Srinath Perur, was included by The New York Times in their listing of the best books of 2017 and nominated for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the International Dublin Literary Award, it made many an Indian chest swell with pride. Other famous prizes such as the Katha Awards and the Crossword Translation Award have been acknowledging and encouraging regional writing and their translations for nearly 20 years.

Found in translation

Some of the most notable translated works to have received the Crossword Translation Award are Karukku by Bama — translated by Lakshmi Holmström, Kesavan’s Lamentations by M Mukundan — translated by Gita Krishnankutty, Chowringhee by Sankar — translated by Arunava Sinha, T’ta Professor by Manohar Shyam Joshi – translated by Ira Pande, A Life In Words by Ismat Chugtai – translated by M Asaduddin, and A Preface to Man by Subash Chandran – translated by Fathima EV.

These prizes recognise some of the best translators in India, many of whom have made translation their life’s mission. Despite the paltry monetary incentives, these prolific translators continue to bridge the divide of language simply for the love of literature. Without their zeal, the beauty and riches of regional work would remain inaccessible to most of us. An urban millennial, for example, wouldn’t dream of picking up a Mahashweta Devi, an Ashoka Mitran, a Saadat Hasan Manto or a G Sankara Kurup. Thanks to the likes of Shanta Gokhale, Lakshmi Holmström, Jason Grunebaum, Arunava Sinha, Rakshanda Jalil, Jerry Pinto, and Rita Kothari, the cream of Indian literary crop is available to the new generation of Indian readers, many of whom are comfortable only with English.

Smells like home

So what’s drawing readers towards these stories? How are they different from Indian English writing? Noted translator, Arunava Sinha says, “I find non-English fiction from India much less inclined to grandstand than English fiction. It’s much more earthy and real, much closer to the lives of the people it features. The writers do not insert themselves as performers. English fiction somehow draws more attention to the texture of the prose. When the writing is good, and the material is honest, it all comes together, but that’s rare.” Sinha recommends Hangwoman by K R Meera, translated by J Devika for a first timer. “For all the qualities that non-English fiction has, and English fiction doesn’t.”